What is a fruit?

This is one of my favorite times of year, when all of the fresh food flows off the fields. Most of all, I love the fruit. First the blueberries, now the peaches. Blueberries may be my favorite fruit. They are so delicious, but maybe because they are native to New Jersey, where I live. Of course, being a plant ecologist and amateur botanist, my interest in fruits extends beyond smoothies and snacks (though I love those very much). I find it fascinating to look at how fruits form from the flower and how fruits vary endlessly while all coming from the same basic template.

What we think of as a fruit—sweet, succulent, juicy, tangy—is a culinary fruit. Botanically, a fruit is a structure that is composed of seeds surrounded by the tissues of the ovary. All flowering plants (angiosperms) make fruit, whether or not it looks tasty to you. The tissues of the ovary are both protective and sometimes attractive to animals who help disperse the seeds. In general, there are three layers to the ovary: an inner, middle, and outer layer. The outer layer is typically the skin or rind, the middle layer is the juicy, fruity bit, and the inner layer lines the seed. This basic layout applies to most fruits, however different they may appear. Some fruits take major liberties with this scheme and incorporate other parts of the flower into their designs.

Diagram of three familiar vegetables, from flower to fruit

Berries

Fleshy fruits are the ones that come to mind first when we think of fruits. In botany, most any fleshy fruit containing one or more seed is some kind of “berry.” In a single ovary from a single flower produces a single fruit. Blueberries, cranberries, and elderberries are good examples. Others in this category include melons, grapes, persimmons, and kiwis. Tomatoes, cucumbers, and summer squash are culinary vegetables that are also botanical “berries.” They aren’t sweet, but they have the same layers— outer skin, tender flesh, seeds—as the sweeter fruits. Remember, these layers all come from the flower, mother of fruit. If you have ever grown squash, picture that huge, orange flower that becomes a long, green zucchini. You can see them in the garden with the flower petals still intact. Once the petals wither, there is still a mark on the bottom of the squash we typically cut off while chopping where the petals and pistil attached.

Prickly pear (Opuntia humifusa) and Mayapple (Podopyllum petlatum) are two New Jersey native plants that produce fruits that are also botanically considered berries. They are actually edible for humans too!

Peaches are also berries, so when I went peach picking this weekend, I was actually berry picking (haha). Peaches, and other stonefruit (plums, apricots, cherries) are great demonstrations of the layers of tissue from the ovary. The fuzzy skin of the peach is the exocarp, the yellow flesh is the mesocarp. The weird porous, hard pit is the endocarp and encloses the seed. That hard inner layer of the fruit gives stonefruit its name. This type of berry is technically called a “drupe.” Avocados, mangos, and olives also fall into this category.

Rasperries and purple-flowered raspberries or thimbleberries, below, are not straightforward berries in a botanical sense. They are “aggregate fruits.” Each little raspberry ball is formed from a separate ovary from the same flower. You can see on the flowers that there are lots of separate male and female parts that lead to a collective of tiny fruits. The little wiggly hairs on raspberries are the withered individual pistils from the flower. All of the separate little fruits from one flower crush together to form a unit: a raspberry.

My other favorite fruit is a milkweed pod. I love the strange teardrop shape and bumpy surface. Before they are ripe, peel them off the plant and watch the white sap ooze from the stem. In the fall, I open them up and play with the silky fibers attached to the seeds. Dry fruits like milkweed pods are the range of fruits that we don’t typically think of as fruits. They are also made of tissues of the ovary, but rather than forming tempting flesh for an animal to eat, they serve other purposes.

Nut is both a botanical and culinary category. A botanical nut has one large seed and is surrounded by a shell composed of hardened ovary tissues. With the fleshy fruits, we eat the ripened ovary tissues, whereas with nuts we eat the seed. The hard, protective layer is why we need a nutcracker to get to the tasty seed. The hickory (Carya cordiformis or Carya glabra), below, has a green outer layer with a hardened endocarp surrounding the seed. Squirrels are equipped with sharp incisors to get past security.

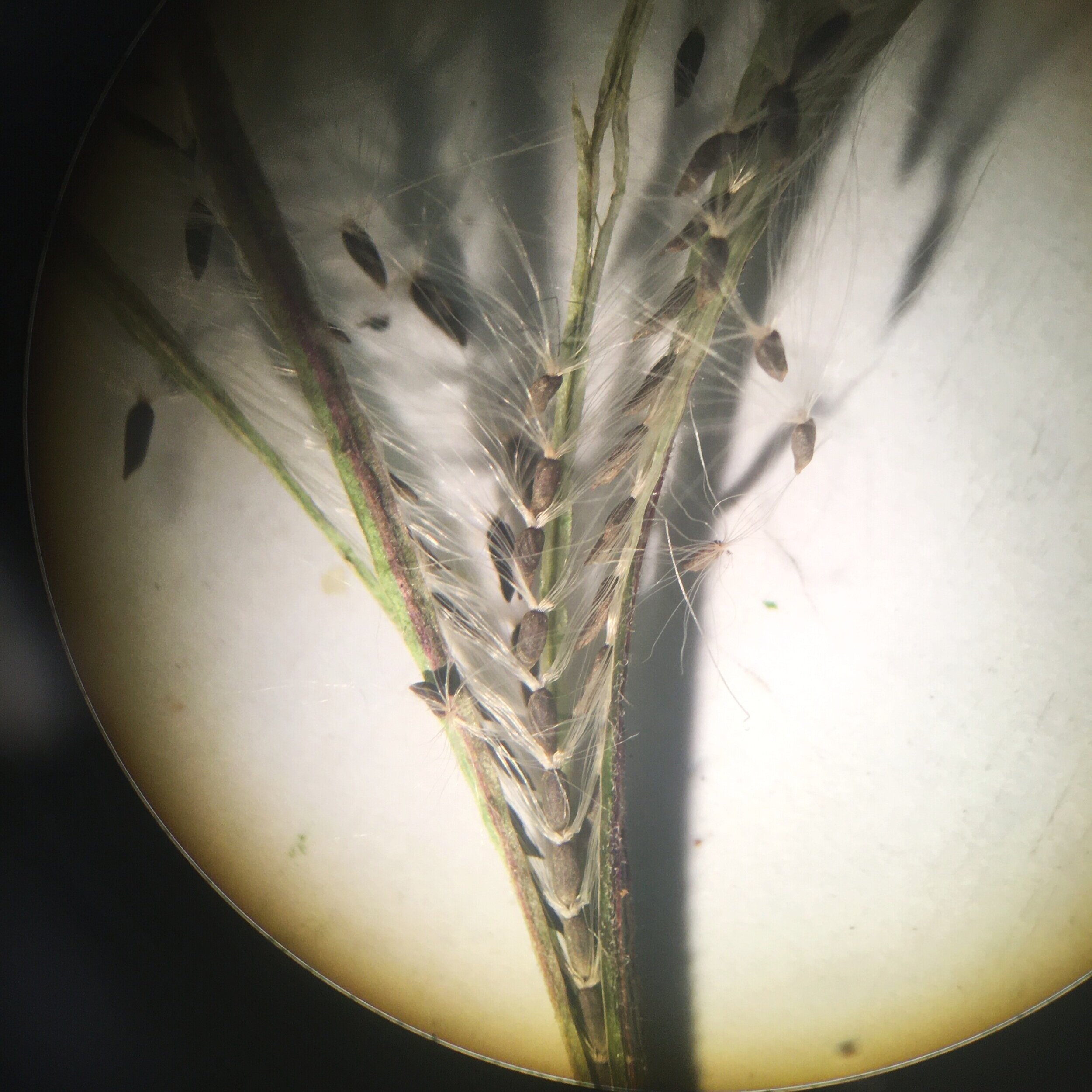

Capsules are seed pods that contain multiple seeds. The seed pod is composed of ovary tissues. Some capsules burst open and spray their seeds around ballistically. Other capsules must be knawed open like a nut. The spring flowers below (spring beauties—Claytonia virginica, bloodroot—Sanguinaria canadensis, and blue-eyed grass—Sisyrinchium angustifolium) all have dehiscent capsules, meaning they split open when ripe. The capsule protects the seeds until then. The dry capsules of common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) and willowherb (Epilobium ciliatum) have split to spill out the dry, mature seeds onto the wind.

The fruit of some trees is meant to float on the wind or water. Maples (Acer species) have samaras, dry helicopters that spin the seeds away from the parent tree. Other dry fruits, achenes, are like tiny nuts. Often, these are so small that we might just think they are naked seeds. Sunflower seeds are an example of this type of fruit. The tasty seed itself is protected by the black and white striped case—the ripened tissues of the ovary. A sunflower seed is a large example of an achene, but many are tiny, like the specks from the green bulrush (Scirpus atrovirens) or the exposed fluff of Aster family flowers in the fall. (Goldenrod—Solidago canadensis, and New York ironweed—Vernonia novaboracensis).

These are all fruits. As with most things, fruit classification is a fractal endeavor. The closer you look, the more each type splits into more specific types. There are legumes, siliques, schizocarps, utricles, caryopses, pomes, and hesperidia, to name but a few. The next time to you eat a fruit, see if you can trace it’s origins. Is there a trace of the petals or style from the flower? Can you differentiate ovary layers—exocarp, mesocarp, and endocarp? Which part is the seed? Can you access the seed with your bare hands or mouth? And now that you have a broader perspective, what’s your favorite fruit?